As COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc on the world, and in particular in the United States, the status of many industries and institutions are in tenuous conditions. With economic instability increasing every week and a lack of prudent government leadership, it is no surprise that thousands of businesses will permanently close by the end of this year. More worrisome is that millions of people will be adversely affected, irrespective if they catch the coronavirus. One such industry I want to focus on is collegiate athletics and the future of student-athletes. Though not the most pressing industry that deserves attention, it is a subject that points to a larger problem in our society. Specifically, I want to propose an alternative college sports model that seeks to address issues relating to compensation, employment, name, image, likeness (NIL), and amateurism.

Athlete compensation is the most pressing challenge facing college sports.

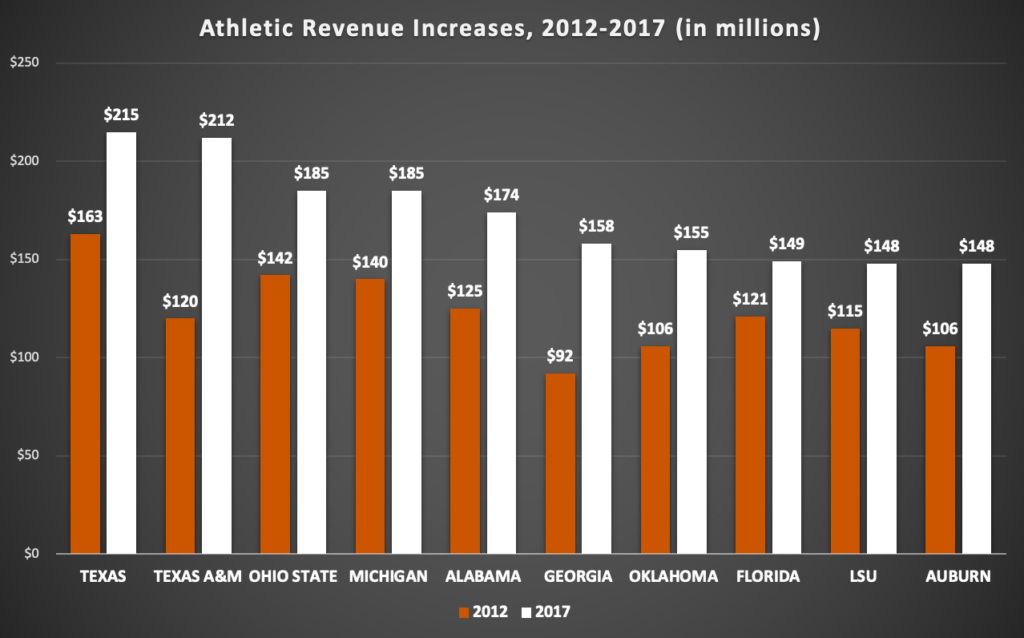

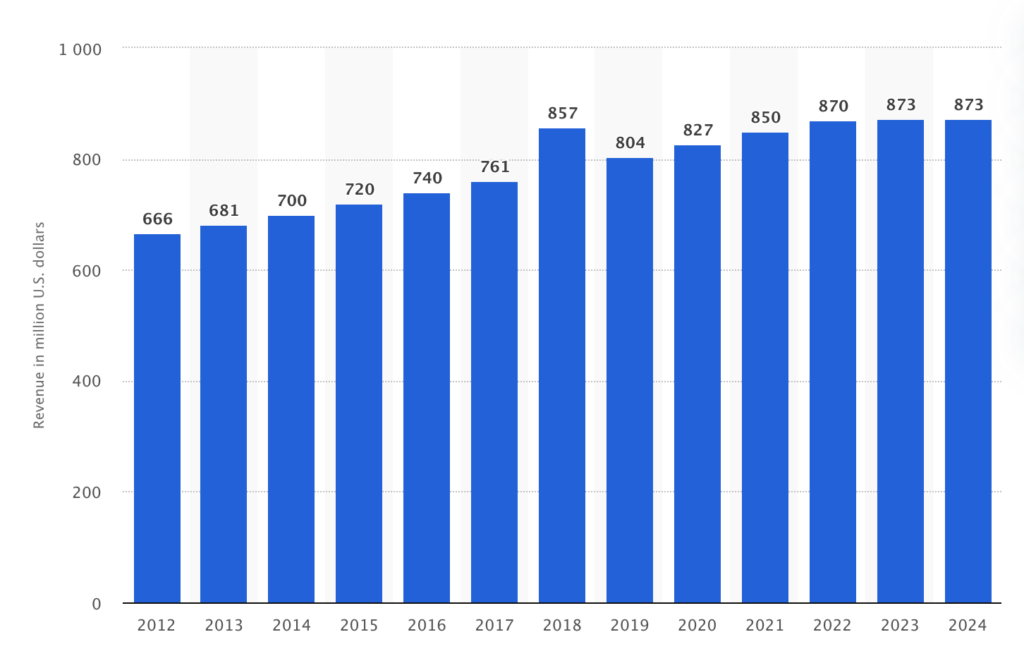

As universities rake in more and more money from TV deals, licensing rights, and ticket sales, greater attention is being paid to unfair compensation of student-athletes. While not all sports, nor all schools, are making record revenues, many of the high-profile education institutions are – including my current school, the University of Texas at Austin. Additionally, the NCAA (the highest governing body of college athletics), has increasingly turned out high revenue from broadcasting and licensing rights.

Student-athletes, the thinking goes, are afforded non-monetary benefits like scholarships; facilities, for which they are the main benefactors, are constantly updated; and athletes are given access to premium opportunities such as tutoring services and exclusive networking. Nevertheless, these student-athletes receive no direct recompense from the various revenue streams they help produce. Football players do not receive a cut of ticket transactions; softball players do not receive a share of jersey sales; basketball players do not get a slice of broadcast media rights deals. It is no wonder why so many have labeled this arrangement as exploitative.

And more crippling, student-athletes are not allowed to seek employment or take payments while competing in intercollegiate athletics – whether from their university or from third party entities. A huge sticking point with this clause is that athletes cannot make money off of their name, image, or likeness (NIL). Fundamentally, this means that student-athletes cannot receive or take payments based on their own attributes such as their signatures, photographs, or appearances. The NCAA would consider it a violation if, for example, Tim Tebow was paid for appearing in a car dealership commercial while he played for the University of Florida from 2006 to 2009.

Like many, I have evolved on this issue. Previously, I maintained that intercollegiate athletics in the United States holds a unique status which enhanced the overall educational experience of student-athletes. Such a status provided adequate compensation for athletes’ sacrifice (in time, energy, social life, etc.) and their (mainly monetary) contributions. This line of thinking was also supported by my belief that, if a student wanted to develop their athletic skill in order to compete professionally, there were enough semi-professional alternatives outside college athletics that he/she could take advantage of.

Essentially my argument was that the system of American college sports did not need to be remodeled because it adequately compensated athletes, and there were sufficient alternatives outside intercollegiate athletics that allowed players to continue their development and receive traditional payment. However, today my thinking on college athletics, NIL, and developmental amateurism is considerably different. Before I elucidate a model that can address the aforementioned problems, we need to establish the employee/employer relation that student-athletes find themselves in.

The Employee Test

Student-athletes provide an undeniable and direct benefit to universities. Student-athletes represent universities in athletic competitions and, in turn, universities use their labor to collect revenues in the form of ticket sales, broadcast media, licensing deals, and much more. There are some (my previous self included) that argue that scholarships, academic resources, free meals, and the like, is adequate compensation for their labor; and to that argument, I have no rebuttal. I can not objectively dispute that claim. However, most people are a little more progressive in their beliefs about college athletics. I have found that a preponderance of people believe the current model of college sports does not adequately compensate student-athletes, but they do not think payment should come directly from universities.

![No money, no gifts, no cars, no endorsement deals… Tell me again, why are we doing this?

[Two college athletes are pulling a car donned with the NCAA flag]

For an education, but I'm not feeling too smart.](https://thestipulation.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Screen-Shot-2020-08-11-at-11.41.30-PM-1024x711.png)

To settle this impasse, any model that seeks to relieve grievances relating to NIL or student-athlete payment needs to first answer the “Employee” question. That is, “What is an employee and do student-athletes meet said standard in relation to their university?” According to most labor departments/agencies (governmental or otherwise), individuals are considered employees if they/their: Agree to a written or implied contract, perform a service, and actions are controlled by a supervisor, manager, or amorphous employer.

If we seriously apply this test to student-athletes, we will find that they are manifestly employees of their university:

(1) Student-athletes have to sign a contract with their university and be registered with the NCAA Eligibility Center. (2) Student-Athletes perform a service by competing in athletics/sports on behalf of their university. (3) Student Athletes must adhere to rules and mandates by not only their coaches and professors, but also by their athletic conference (SEC, Big XII, etc.) and the NCAA.

I think on some level most people recognize this because many are willingly acknowledge how what student-athletes do is akin to a full time job. In fact, the general counsel of Chicago’s National Labor Rights Board wrote that many student-athletes should be considered employees. We can quibble about the best way to compensate employees, but we cannot ignore the fact that student-athletes are employees of their chosen university.

Once we acknowledge the employee status of student-athletes, the next question becomes what model do we adopt in order for student-athletes to be adequately and monetarily compensated? The best model would accomplish two tasks: Firstly, it would explicitly define the employee-employer relation I previously mentioned. And secondly, it would ensure the fair market compensation of athletes associated with their university.

I favor an approach closer to that of a semi-professional club sports model.

The ultimate guiding-light for this model is for athletes to be able to make money just like their non-athlete student counterparts. Though not fully fleshed out, I’ll describe the markers that I think give a good outline of this alternative college sports model. I’ll use the University of Texas as an example for clarity, but this model would need to be adopted by scores of Power 5 institutes in order to work. The model, abridged, is as follows:

- The University of Texas (and many others) would leave the NCAA and “eliminate” most, if not all, of their varsity teams.

- The University would restructure Intercollegiate Athletics such that it moves from a department within the University to a distinct subsidiary of the University. For the sake of this exercise, I’ll refer to this new entity as Longhorn LLC.

- Longhorn LLC would establish club teams on behalf of the University of Texas. These club teams would, in effect, take the place of the teams that were previously eliminated. They would compete against other club teams.

However, there are some major distinctions. First, the mission of these club teams is to compete in the gap between high school athletics and professional athletics – thus making it a semi-professional or developmental organization. It is explicitly not an educational endeavor. And, as a subsidiary of the University, Longhorn LLC would operate to the extinct that they maintain solvency and provide intangible benefits (e.g. promotion of traditions and recruiting prowess).

Ideally, these club teams would be made up of people who are currently attending a university, but this would not mandatory. Anyone who could competitively benefit the team (and abides by standard player conduct rules) would be eligible.

Players would be paid a salary by Longhorn LLC and receive health benefits comparable to other University employees. And to the issue of NIL, these athletes would be able to enter into endorsement/sponsorship deals as long as it does not interfere with the operations, integrity, or interests of Longhorn LLC or the University of Texas. More importantly, players could negotiate their contracts, thus, in theory, getting their fair market value.

It is not lost on me the problems of this plan.

As alluded to before, this model would need to be adopted by scores, if not hundreds of universities in order to successfully work. Additionally, it is unquestionable that some, if not all, non-revenue producing sports would be cast into a state of peril. Financial weak sports such as track & field or soccer may be relegated to glorified intramural competitions – or cut altogether. And unfortunately, under this model, women’s equity in sport would likely take a huge blow. I admit that these are uncomfortable consequences, but they are consequences we should be willing to take for the sake of athletes’ rights, competitive fairness, and honesty on the issue of amateurism.

Under this model, athletes who have the ability to reach the professional level in their chosen sport can make money without being constrained by the NCAA’s exploitative standards. Ultimately, a club sports model promotes athletes seizing their fair market value – especially through NIL – and rightfully solidifies the semi-professional status of college sports. These are laudable objectives that ought to be explored without fear or reticence.